An earlier version of this essay appeared in Gun Digest

The gun discussed is currently in the collection at the National Firearms Museum

All properly trained shooters and hunters are aware that an accidental discharge of a firearm can have disastrous consequences, and take pains to avoid having one. One way to do this is to equip a gun with some sort of disabling device. This is especially important in the case of handguns, whose ergonomics are such that picking one up more or less immediately puts it into “firing mode.”

Most (not all) autoloading handguns are equipped with a manual safety of some kind that has to be positively put “off” by the shooter before discharging, but there’s a popular misconception—often stated in training courses!—that “Autoloaders have safeties; revolvers don’t,” which is certainly incorrect. While most revolvers lack a manual safety device (leaving aside the ones on current production guns mandated by law) revolvers that do have them have been around for quite a long time: it’s by no means unusual to encounter a mechanical safety catch on revolvers, especially some made in Europe well into the 20th Century.

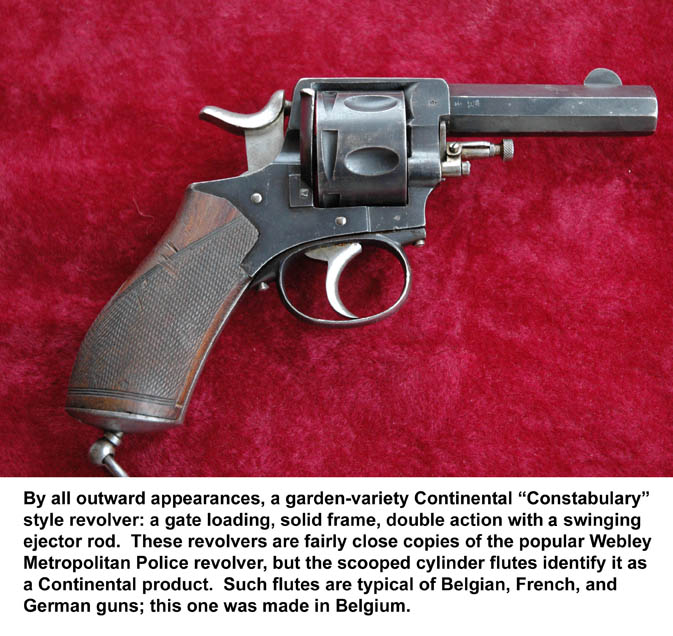

Some years ago I purchased a revolver of the “Constabulary” type: a prototypical “Constabulary” has a saw-handle grip, and is a solid frame, gate-loading double action with a swinging under-barrel ejector rod. The best example is the Webley Metropolitan Police—used by the British Constabulary, hence the generic name for similar guns—a design widely copied by Continental gun makers. Constabularies usually have a lanyard ring as well, consistent with normal European police practice.

Many Continental Constabularies were made for export, but many were issued to police forces. Mine was made in Belgium and is in the 9.4mm “Dutch Service” caliber. Externally it is virtually identical in appearance to guns marked “Maastricht” that are known to have been issued to Dutch police forces. Internally it differs considerably.

Many Continental Constabularies were made for export, but many were issued to police forces. Mine was made in Belgium and is in the 9.4mm “Dutch Service” caliber. Externally it is virtually identical in appearance to guns marked “Maastricht” that are known to have been issued to Dutch police forces. Internally it differs considerably.

When I received it the action seemed to be completely inoperable. Neither the trigger nor the hammer budged, no matter how hard I pulled. Thinking that the internal lockwork was frozen with rust, I took off the grip, and there I saw the answer to one question, but encountered an even more fascinating one. Namely, “What have I got here?”

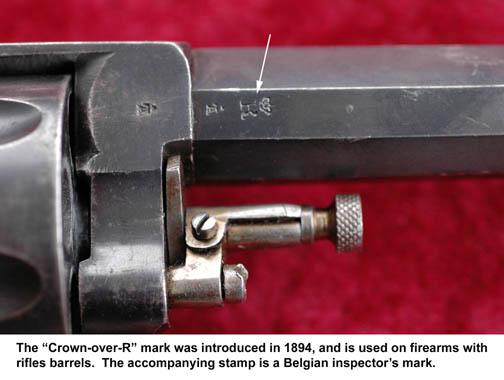

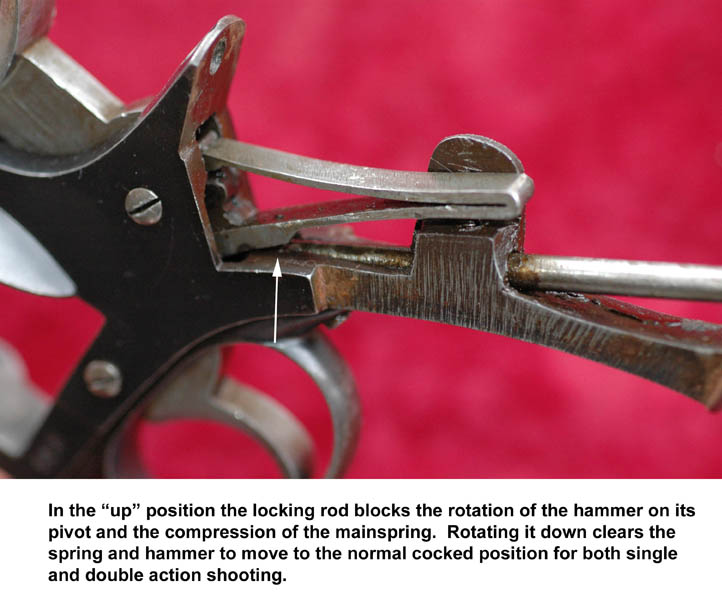

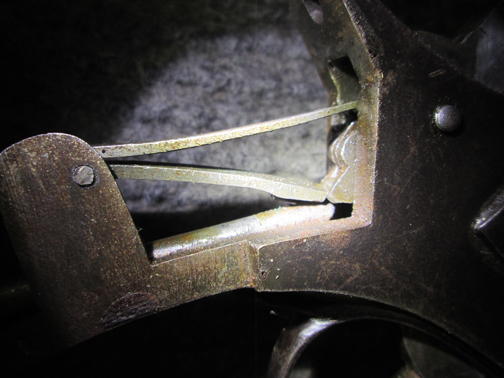

The lanyard swivel is not (as most are) free rotating. It is attached to the lower end of a long rod that passes through a boss cast into the frame. This rod is located behind the hammer pivot in such a way that when elevated to a certain position it completely blocks the hammer’s movement.

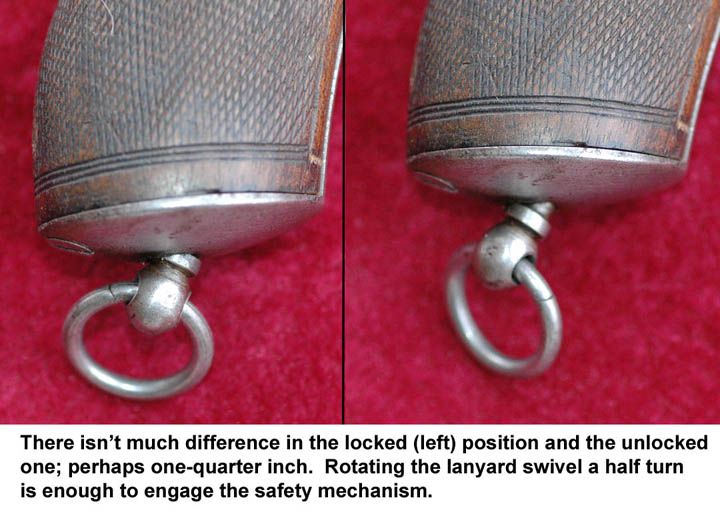

When the lanyard swivel is rotated half a turn counterclockwise, the rod moves down out of the way of the hammer and the action works smoothly. When rotated the same amount clockwise, the rod moves up behind the hammer and locks the entire action tightly. The total movement is perhaps a quarter-inch from the bottom position to the top. It’s a little cumbersome, perhaps, but about as positive a safety device as could be imagined. The rod has a helical groove machined into it that slides over a small stud concealed inside the boss. Turning the lanyard ring thus imparts a screw-type motion and operates the mechanism.

To all outward appearances the gun is an ordinary Continental Constabulary, but that safety is unique in my experience. Constabularies with safeties usually have them mounted somewhere on the frame; they often work simply by blocking the cylinder’s rotation; if the lockwork is blocked, the safety lever is on the left side of the frame convenient to the shooter’s thumb. Examples of this sort of side mounted safety are easy to find.

Never having encountered a safety that worked the way this one did, I wrote to several noted collectors and major collector’s magazines to ask about its origins but was met with shrugs or the reply that “It’s probably a removable ejector rod,” which it most certainly is not. So I went on a hunt to see what I could find in old patent records. I knew a device like this had to be the subject of a patent.

Never having encountered a safety that worked the way this one did, I wrote to several noted collectors and major collector’s magazines to ask about its origins but was met with shrugs or the reply that “It’s probably a removable ejector rod,” which it most certainly is not. So I went on a hunt to see what I could find in old patent records. I knew a device like this had to be the subject of a patent.

A day or two at the National Firearms Museums Library, where I was courteously granted access to a voluminous book of firearms patents from all over the world, showed me several safeties that were similar, but all differing in some essential characteristic. These old patents, however, had one thing in common: they were almost all the product of the mind of one “Joseph Tambour,” originally of Vienna, Austria; and later of Nanterre, France.

In all, Tambour held 40+ patents issued between 1899 and 1925, all but one dealing with firearms safeties. Since he usually described himself as “..a subject of his Majesty the Emperor Franz Josef,” and therefore was probably born in Austria-Hungary, a letter to the Vienna State Archives elicited the information that he was born July 17, 1857 in Lemburg. The official record describes his occupation as “Waffentechniker” (a “weapon technician”) and gives some details of his places of residence through April 1930. No date of death has been established, but I believe he may have died about that time.

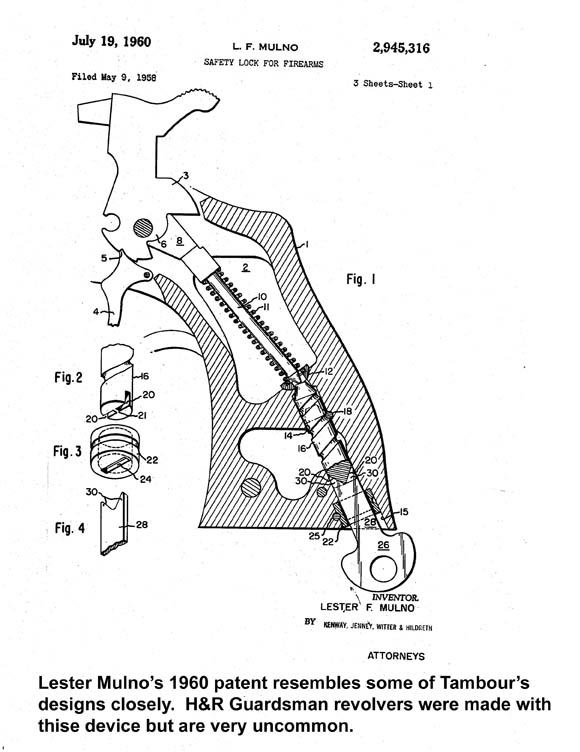

I continued to search old records, contact collectors, and to haunt gun shows and auction sites looking for a similar revolver, and came up with nothing that resembled the safety on my revolver. Well, that is, nearly nothing. Then I found US Patent #2,945,316, issued in July of 1960 to Lester F. Mulno; and assigned to his employer, Harrington & Richardson of Worcester, Massachusetts.

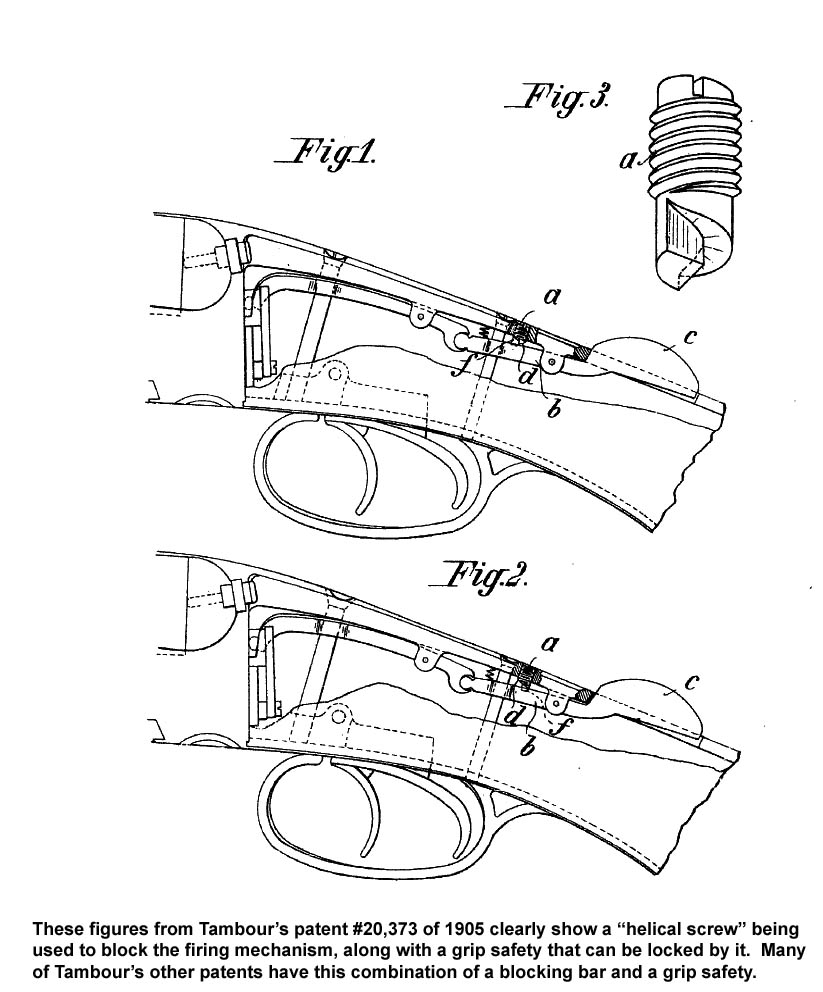

H&R briefly marketed a variant of their Model 732 “Guardsman” revolver employing the Mulno device, which bears an eerie resemblance to the safety on my revolver and works in exactly the same way. A rod in the grip rotates in a screw-type motion, rising up to block the movement of the internal lock parts. Mulno’s version incorporates a key-activated lock to control the movement of the rod rather than a lanyard swivel. Mulno actually cited Tambour’s Austrian patent #20,373, issued in June of 1905; it is in fact the only patent he referenced, but nowhere in the text is the relationship of the two devices explained.

H&R briefly marketed a variant of their Model 732 “Guardsman” revolver employing the Mulno device, which bears an eerie resemblance to the safety on my revolver and works in exactly the same way. A rod in the grip rotates in a screw-type motion, rising up to block the movement of the internal lock parts. Mulno’s version incorporates a key-activated lock to control the movement of the rod rather than a lanyard swivel. Mulno actually cited Tambour’s Austrian patent #20,373, issued in June of 1905; it is in fact the only patent he referenced, but nowhere in the text is the relationship of the two devices explained.

Mulno’s claims for his device could be applied to my gun:

10. [a]…releasable locking means carried by said frame comprising a threaded locking member movable toward and away from said firing member…engageable with [the] firing member so as to hold it in a position such that it cannot fire,

11. [a] …releasable locking means for positively obstructing movement of the firing means…comprising a rotatable threaded locking member within the frame and movable toward and away from locking engagement with the firing means

12. [a]…releasable locking means…comprising a threaded locking member carried by the firearm and movable toward and away from said firing member, the locking member having an inner end portion engageable with the firing member, to lock said firing member against firing movement… the locking member has a steep pitch thread so that approximately, a single rotation of the locking member is sufficient to move the locking member between locking and release position….the threaded engagement…with the…frame is provided by a pin disposed in the frame generally transverse to the axis of rotation of the locking member and intersecting the thread groove thereof.

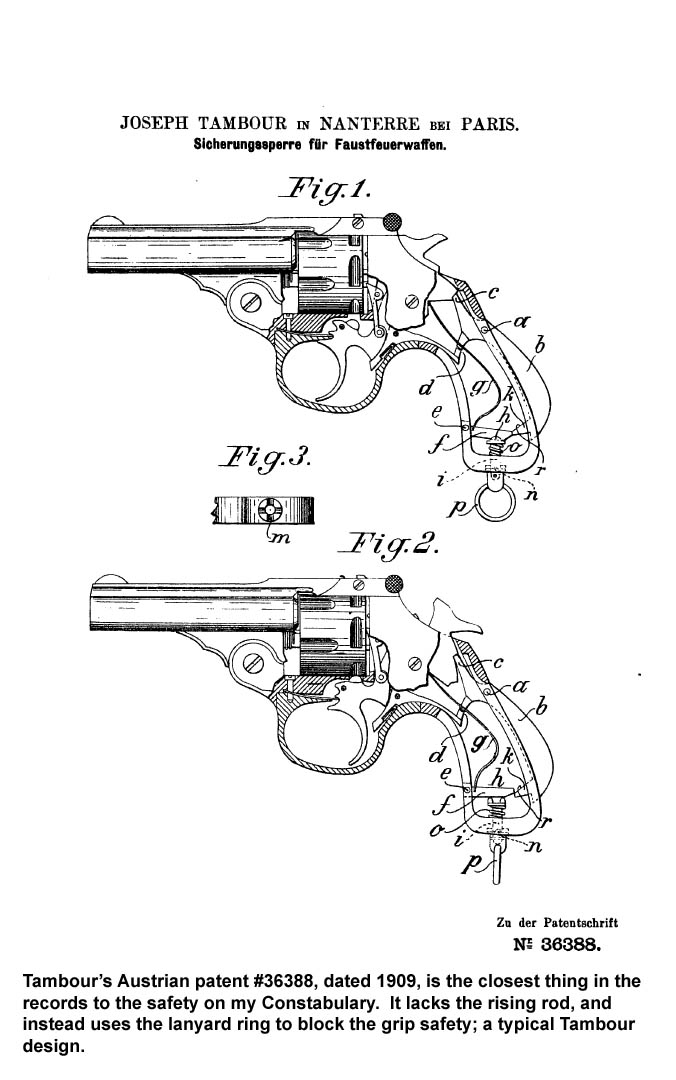

Mulno’s design—and the safety on my revolver—bears an even closer resemblance to another of Tambour’s Austrian patents: #36388, issued in February 1909, a drawing from which clearly shows a screw-in lanyard loop attached to a helical screw, rising to block the grip safety that controls the firing mechanism of a revolver. Add the rising rod and eliminate the grip safety, and it would be identical to mine. Mulno must have been aware of this patent but makes no reference to it.

Mulno’s design—and the safety on my revolver—bears an even closer resemblance to another of Tambour’s Austrian patents: #36388, issued in February 1909, a drawing from which clearly shows a screw-in lanyard loop attached to a helical screw, rising to block the grip safety that controls the firing mechanism of a revolver. Add the rising rod and eliminate the grip safety, and it would be identical to mine. Mulno must have been aware of this patent but makes no reference to it.

Based on the research I’ve done I have to conclude that the safety mechanism on my Constabulary is a Tambour design: there are simply too many similarities to his other patents for it to be the work of some other inventor, although it’s possible that someone who worked with Tambour might have come up with the idea. But the inability to locate any patent that exactly corresponds raises a couple of questions.

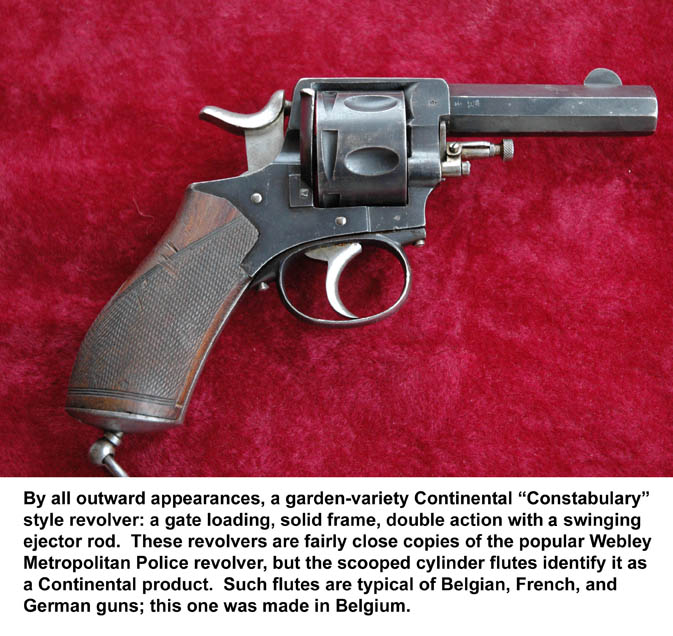

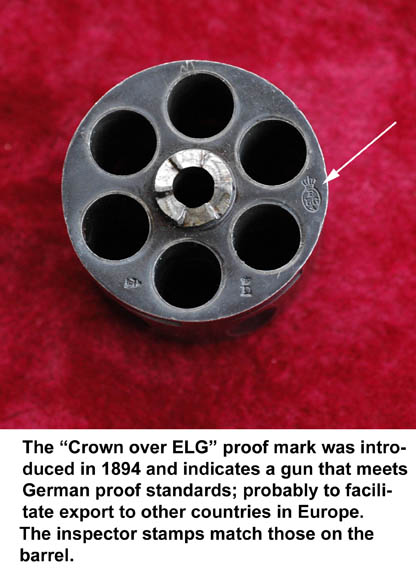

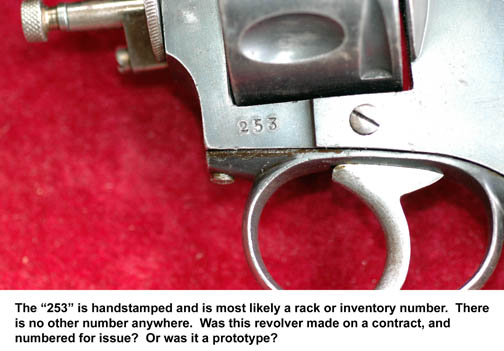

Could this odd revolver be a tool room prototype incorporating a new safety mechanism? It has no indication of the maker, none whatever: it has Liege proof marks on the cylinder face, Belgian inspector’s marks on the barrel, and a laconic “253” hand stamped on the left side of the frame. Half a dozen companies in Belgium could have made it, but there is no way to know which one it was. Another question is whom Tambour might have been working for. Unlike Lester Mulno’s patents, Tambour’s have no indication of an assignee.

The Liege proof is one that was first used in 1894: the “Crown-over-R” mark indicates a rifled barrel, and went into use in 1894 as well. Thus the gun cannot be older than 1894, and could be significantly newer. Constabularies were made well into the 1920’s, as the design was very popular.

The Liege proof is one that was first used in 1894: the “Crown-over-R” mark indicates a rifled barrel, and went into use in 1894 as well. Thus the gun cannot be older than 1894, and could be significantly newer. Constabularies were made well into the 1920’s, as the design was very popular.

The “253” which is clearly stamped with individual numeral dies, I believe to be a rack or inventory number, not a serial number. If this assumption is correct, given that the caliber is that used by Dutch civilian police forces, could it have been part of an order sold to some municipality, or one of a number of guns that were being used in “field trials”?

Was it made for export? If so, where to? Belgian makers enjoyed a world-wide market. Probably not in the reaches of the Dutch colonial empire, however. There they used a somewhat longer version of the 9.4 round, which implies that this revolver was not intended for use in the East Indies, but rather in Europe. The Dutch arms making capabilities were rather limited, and they are known to have contracted with the sizeable Belgian arms industry for their needs.

Was Tambour planning to file yet another patent to cover this safety device, but perhaps died before he filed? Was Mulno aware of this safety mechanism when he designed his own?

Was Tambour planning to file yet another patent to cover this safety device, but perhaps died before he filed? Was Mulno aware of this safety mechanism when he designed his own?

One of the frustrating aspects of arms collecting is that often the people who can answer specific questions are no longer with us; and records usually don’t exist. Tambour died long ago; Mr Mulno died in the early 1990’s. Luckily the US Patent Office database, and the European equivalent, are searchable on line, but H&R is out of business. Their successors have no old records, and access to copies of old factory records turned in to the BATF require a request under the Freedom of Information Act. This can take years to be granted. (And while this might indicate how many “Guardsman” guns were made with the Mulno device—it can’t have been very many—it probably wouldn’t shed much light on how and where Mulno got his ideas.)

I have looked for years for another example of a gun with such a safety, contacting many collectors and high-end auction sites, and have found nothing like it. On occasion someone says, “Oh, yes, I’ve seen one like that,” but if in fact another example exists, I’ve been unable to locate it for examination. If any of NRVO's readership knows of such a gun, and/or where I can find an H&R Guardsman with the Mulno lock, I would very much appreciate having the information. I can be contacted through the opening page of the site any time, and extend thanks to the community of gun collectors for any help you can provide.

ADDENDUM, JULY 9, 2018

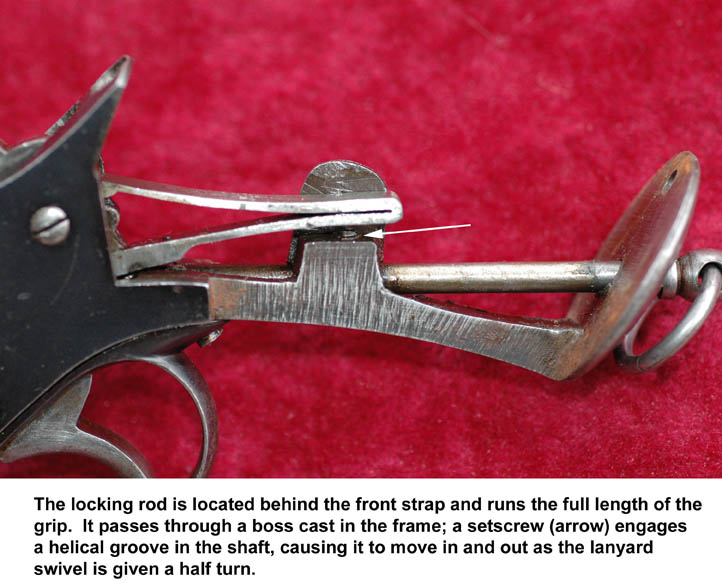

Since this article was published, I have been alerted to the existence of at least two more examples of revolvers with this type of lanyard ring safety. The images below were very kindly provided by Mike Allee, the proprietor of Gunsmithing Only in Shawnee, Kansas. He had advertised a revolver on Gunauction.com which was identical to mine, and upon request sent me images of his gun with the grips removed. As will immediately be seen, the gun he owns is identical to the one described above, with the exception of the presence of Belgian proof marks. I was certain my revolver was Belgian but am very glad to have this confirmation.

Neither mine nor his revolver have any indication of maker, unfortunately. I will be very grateful if anyone who can provide further information, or who has a gun with this type of safety, would please contact me.

ADDENDUM, MARCH 2, 2021

Another key-locked H&R revolver has been brought to my attention. A Model 939 "Ultra Sidekick" in .22 caliber, offered for sale by Oregon Guns via the Gun Auction web site. The beautiful photos shown here, courtesy of Mr David Warner of Oregon Guns, clearly show the location of the lock in the butt. Serialization tables for H&R indicate this revolver was made in 1973. I had first read about the key-locking H&R's in the mid to late1960's in Gun World magazine; they were sold under the name "Guardian" in .32 caliber. This example proves the Mulno device was also used on .22's and that the "Sidekick" line used them too. The "Ultra Sidekick" was one of H&R's higher-end guns.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |